Jacob Hamblin

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Jacob Hamblin | |

|---|---|

A restored photo of Hamblin, originally taken c. 1860 | |

| Born | April 2, 1819 Ashtabula County, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | August 31, 1886 (aged 67) Pleasanton, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | Lucinda Taylor, Rachel Judd, Sarah Priscilla Leavitt, Louisa Boneli |

Jacob Hamblin (April 2, 1819 – August 31, 1886) was a Western pioneer, a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and a diplomat to various Native American tribes of the Southwest and Great Basin. He aided European-American settlement of large areas of southern Utah and northern Arizona, where he was seen as an honest broker between Latter-day Saint settlers and the Natives. He is sometimes referred to as the "Buckskin Apostle", or the "Apostle to the Lamanites".[1] In 1958, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[2]

Early life and family

[edit]Hamblin was born in Salem, Ohio, to a family of farmers. He grew up learning farming. He was baptized a member of Church of Christ on March 3, 1842, at the age of 22.[citation needed]

Hamblin and his first wife, Lucinda, had four children. When Hamblin proposed moving west with the Latter-day Saints to the Salt Lake Valley, Lucinda refused to go. In February 1849, Hamblin and Lucinda ended their marriage, and he continued west without her, taking the four children with him. In September, Hamblin met and married Rachel Judd, a widow, in Council Bluffs, Iowa. He and Rachel had five children.[3] Hamblin lived the Mormon doctrine of plural marriage and married Sarah Priscilla Leavitt on September 11, 1857, Eliza Hamblin on February 14, 1863 (with whom he had one child), Clara Melvina Hamblin on Nov. 5, 1876 (their daughter was raised by Priscilla after Eliza left Jacob for Paiute Poinkum), and Louisa Bonelli on November 16, 1865.[citation needed] With Leavitt, he had 14 children and also raised Clara,[citation needed] and, with Bonelli, he had 6 children. Leavitt and Bonelli were sealed to him in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City.[4][5]

Conversion to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and migration west

[edit]As an adult, Hamblin and his family lived in Spring Prairie, Wisconsin. Hamblin was injured and thought he would die of his wound. Hamblin prayed that if he survived, he would serve God the rest of his life. Soon after, a woman knocked on his door who said she had felt called to go to his house. A nurse, she had the medicines and poultices needed, and helped heal Hamblin's wound and saved his life. Hamblin felt Mrs. Campbell, the tall white Nordic looking nurse, was sent to him from God (see autobiography of Jacob Hamblin, "My Life with the Indians"). Note that the first nine pages of Hamblin's autobiography "My Life with the Indians," were omitted in later reprints, so Mormon readers wouldn't know about the beautiful tall white nurse that appeared in Spring Prairie, Wisconsin in 1842, long before Hamblin had any neighbors, there were no nurses within miles of Spring Prairie in 1842. [citation needed]

In his memoir, Hamblin wrote of the moment he decided to support Young:

"On the 8th of August, 1844, I attended a general meeting of the Saints. Elder Rigdon was there, urging his claims to the Presidency of the Church. His voice did not sound like the voice of the true shepherd. When he was about to call a vote of the congregation to sustain him as President of the Church, Elders Brigham Young, Parley P. Pratt and Heber C. Kimball (all members of the Quorum of the Twelve) stepped into the stand. Brigham Young remarked to the congregation: 'I will manage this voting for Elder Rigdon. He does not preside here. This child [meaning himself] will manage this flock for a season.' The voice and gestures of the man were those of the Prophet Joseph. The people, with few exceptions, visibly saw that the mantle of the Prophet Joseph Smith had fallen upon Brigham Young. To some it seemed as though Joseph again stood before them. I arose to my feet and said to a man sitting by me, 'That is the voice of the true shepherd—the chief of the Apostles'."[6][7]

Hamblin was a Mormon pioneer and in 1850 settled in Tooele, near Salt Lake City. He became well known for creating good relations between the white settlers and Indians. After an altercation, when his gun failed to fire as he shot at an Indian, Hamblin said God had revealed he was to be a "messenger of peace" to the Indians, and that if he did not thirst for their blood, he should never fall by their hands.[8] In 1854, Hamblin was called by Young to serve a mission to the southern Paiute Indians and settled at Santa Clara in the vicinity of the modern city of St. George, Utah.[citation needed]

Hamblin's first home in Santa Clara was destroyed by a flash flood. His second wife, Rachael, saved one of their young children from drowning, but the child died soon after from exposure. Hamblin had built two rocking chairs, one for each daughter. He painted one red and one yellow. His youngest daughter got the red one. His other daughter coveted the red one and stole it from his youngest girl. The young girl found the red chair her father Jacob had given her, took it outside, sat in the snow with it, and died of exposure in that little rocking chair. Rachael never fully recovered from the exposure she got from the flood. Swearing to avoid the risk of flood, Hamblin built a new home on a hill in Santa Clara. Owned today by the LDS Church, the house is operated as a museum.[citation needed]

Utah War and the Mountain Meadows massacre

[edit]

In August 1857, Brigham Young made Hamblin president of the Santa Clara Indian Mission. Young directed Hamblin by letter to

continue the conciliatory policy towards the Indians which I have ever commended, and seek by works of righteousness to obtain their love and confidence. Omit promises where you are not sure you can fill them; and seek to unite the hearts of the brethren on that mission, and let all under your direction be united together in holy bonds of love and unity.[9]

Young had become aware in July of an approaching United States army ordered to invade the Utah Territory to put down a supposed "rebellion" among the Mormons. Anticipating what would become known as the Utah War, Young urged Hamblin to "not permit the brethren to part with their guns and ammunition, but save them against the hour of need."[9] He wrote to Hamblin that the Indians "must learn to help us or the United States will kill us both."[10]

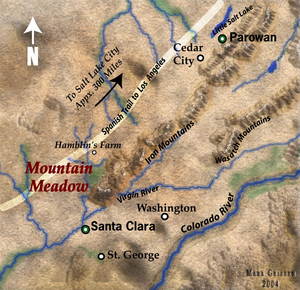

In late August, Hamblin traveled north to Salt Lake City with George A. Smith, of the church's First Presidency, who had been dispatched to the southern Mormon colonies to warn of the approaching U.S. army and recommend against colonists trading with non-Mormons, then traveling through their territory. At Corn Creek near Fillmore, Utah, Smith, Hamblin, and Thales Haskell encountered the Baker–Fancher party, a wagon train of Arkansans en route to California. Hamblin suggested to them that they stop further south in Mountain Meadows, where he maintained a homestead at a traditional stopping point on the Old Spanish Trail from New Mexico to California.[citation needed]

Hamblin and his party continued on to Salt Lake City, where he stayed for roughly a week to "conduct Indian business and take a plural wife".[11] This "Indian business" included bringing a delegation of Southern Paiute to meet with LDS Church leaders. In Salt Lake City, Hamblin reported later that he was told that the Fanchers had "behaved badly" and had "robbed hen-roosts, and been guilty of other irregularities, and had used abusive language to those who had remonstrated with them. It was also reported that they threatened, when the army came into the north end of the Territory, to get a good outfit from the weaker settlements in the south."[12]

By one account, Hamblin was on his way home and was met by his adopted Indian son, Albert, who recounted the horror of the slaughter of the Baker–Fancher Party in the infamous Mountain Meadows massacre. In fact, on his trail south, he also met John D. Lee who was on his way to Salt Lake City.[13] In both his autobiography and his testimony at the second trial of Lee for the massacre, Hamblin claimed that, to his great distress, Lee admitted to him his role in the killings along with other Mormons, although he placed the blame for the attack on the Paiutes.[13][14] Many[weasel words] accept Hamblin's account of his meeting with Lee because Hamblin was well known for honesty. (Professor A. H. Thompson of the U.S. Geological survey once said, "I would trust my money, my life and my honor in the keeping of Jacob Hamblin, knowing all would be safe").[15]

As Hamblin continued south towards Santa Clara, he was told that a band of Paiutes was planning to attack a second wagon train, the Duke party. Perhaps believing Lee's account that the Indians were primarily responsible for the Mountain Meadows massacre, he quickly returned south to prevent another slaughter. He recounts that he did not himself overtake the wagon train, but – as he had been traveling very quickly without sleep – he sent Samuel Knight and Dudley Leavitt before him. Knight and Leavitt overtook the wagons and were able to negotiate with the Paiutes wherein the Indians took the trains' loose cattle (nearly 500 head) and left the train in peace. Knight and Leavitt continued with the company and saw it safely through to California. Hamblin was later able to return that stock to the Duke party after conferring with those Indians involved.[16][non-primary source needed]

Upon reaching the massacre site, the diary of Sarah Priscilla Leavitt, Hamblin's third wife, recounts the horrors of her lying in the covered wagon as they got to the scene. Although Hamblin warned her to not look out, she peeked for a few seconds, which she always regretted. The remaining children that survived (some accounts say 17, some say 20) were brought to the Hamblin home that night. Sarah cared for three of the children herself. Eventually, federal agents returned all the children to their Arkansas relatives.[17][unreliable source?] Brevet Major J. H. Carelton interviewed Albert, who gave a detailed account of what he saw of the massacre.[18][unreliable source?] Later, he [who?] was found lying face down dead in a cactus. Sarah wrote in her diary that both she and Hamblin felt his knowledge of what really happened at the massacre resulted in his murder.[citation needed]

Hamblin spent the rest of 1857 and early 1858 shepherding non-Mormons through Utah on the trail to California and Mormons returning to Utah from outlying settlements in order to participate in its defense should the army attack.

After the conclusion of the Utah War, Hamblin claims to have been willing to testify to his knowledge of the massacre at the behest of George A. Smith. However, due to the amnesty proclaimed by the President of the United States to the Mormons, the new governor, Alfred Cumming, did not wish to discuss the matter.[19] Hamblin did, however, testify at Lee's second trial for the massacre in 1876.[citation needed]

Later missions to Native Americans

[edit]

In 1858, while he was in Salt Lake City, Hamblin was made a sub-Indian agent.[clarification needed] That same year he was called on a mission to the Moquis (Hopis) of northern Arizona. He traveled southeast through Pipe Springs, crossed the Buckskin Mountain (Kaibab Plateau), and forded the Colorado River at the Crossing of the Fathers which is now under Lake Powell at Padre Bay. This was somewhat north of the later crossing at Lee's Ferry which he discovered.[citation needed] Upon his arrival at the village of Oraibi, he was told by the Hopis that it was prophesied that he and his companions would come and bring the Hopi knowledge which they formerly had.[citation needed] However, they were also told that the Hopi would not cross over the Colorado River to live with the Mormons until the three prophets which had led them to their mesas returned to give them further instructions.[citation needed] (See Hopi mythology). The Hopi also questioned why they should cross the Colorado River to meet the Mormons when they would soon have settlements to their south in any case. At the time, there were no plans for Mormon settlements to the south of the Hopi, although Hamblin helped found Mormon settlements on the Little Colorado River years later.[citation needed]

Hamblin went home, but returned on several occasions to keep up good relations with the Hopi and the Navajo. In 1862, three Hopi men accompanied him to Salt Lake City to meet Brigham Young. In 1870, he brought a minor Hopi leader, Toova, and his wife across the Colorado River to visit the Mormon settlements in southern Utah. Tuba eventually joined the LDS Church, and invited the Mormons to settle near his village of Moencopi where they founded Tuba City, named in honor of their Hopi friend.[citation needed]

Earl Spendlove's article, "Let Me Die in Peace", states that Hamblin originally purchased Eliza, a Paiute from Utah of the Shivwit or Cedar Band, to free her from slavery. Hamblin adopted Eliza (nicknaming her "Suzie"), when she was a teen. Jacob later took wives Priscilla and Louisa, along with Mary Elizabeth, Clara Melvina, Jake (Jacob Jr.), and the rest of his children to Kanab, Utah. A Paiute known as Old Poinkum later married Eliza and took her to New Harmony Valley, Utah. Later, after Priscilla Hamblin left Nutrioso ranch in Arizona, Priscilla Hamblin and Jacob moved to Eagar, then Alpine, Arizona. Louisa Hamblin later wrote to her daughter that she had knit a pair of "pink stockings" for "Eliza's baby", illustrating that Jacob continued to help the Paiute woman he freed from slavery.[citation needed]

Hamblin was an invaluable diplomat between the Latter-day Saints and the Native Americans, surviving numerous dangerous encounters between the two. In 1870, he also acted as an adviser to John Wesley Powell before his second journey through the Grand Canyon. Hamblin acted as a negotiator to ensure safety for Powell's expedition from local Native tribes. Powell related that Hamblin "speaks [the Indians'] language well and has great influence over the Indians in the region round about. He is a silent, reserved man, and when he speaks it is in a slow, quiet way that inspires great awe."[20] Said a Native Chief to Powell, "We believe in Jacob, and look upon you as a father .... We will tell [the other Indians] that [Powell] is Jacob's friend."[20]

Hamblin attributed much of his success with the Indians to his conviction that he "had received from the Lord an assurance that I should never fall by the hands of the Indians, if I did not thirst for their blood."[21] Indeed, on many occasions, Hamblin dealt with hostile Indians with no companion and carrying no weapon to defend himself.[22] During one particularly trying period in 1874, three Navajo were shot by a member of the Butch Cassidy gang[23] in central Utah. Hamblin had previously promised the Navajos they could safely trade with the Mormons in that area, and Mormons were falsely blamed for the killing. Hamblin was asked by Brigham Young to talk with the angry Navajos and avert war, but Hamblin's local bishop made two desperate attempts to keep him from walking into a "certain death-trap". Hamblin refused to return home, stating that "I have been appointed to a mission by the highest authority of God on Earth [Brigham Young]. My life is but of small moment compared with the lives of the Saints and the interests of the Kingdom of God."[23] One eye-witness[24] to the events that followed, reported that "no braver man ever lived". Hamblin offered his rules for dealing with the Indians as follows:[citation needed]

- I never talk anything but the truth to them.

- I think it useless to speak of things they cannot comprehend.

- I strive by all means to never let them see me in a passion.

- Under no circumstances show fear, thereby showing to them that I have a sound heart and a straight tongue.

- Never approach them in an austere manner nor use more words than are necessary to convey my ideas, not in a higher tone of voice than to be distinctly heard.

- Always listen to them when they wish to tell of their grievances, and redress their wrongs, however trifling they may be if possible. If I cannot I let them know I have a desire to do so.

- I never allow them to hear me use profane or obscene language or take any unbecoming course with them.

- I never submit to any unjust demands or submit to coercion under any circumstances, thereby showing them that I govern and am governed by the rule of right not by might.

Hamblin added, "I believe if the rules that I have mentioned were observed there should be little difficulty on our frontier with the Red Man."[citation needed] He treated the Native Americans as intelligent equals. He said, "some people call the Indians superstitious. I admit the fact, but do not think that they are more so than many who call themselves civilized. There are few people who have not received superstitious traditions from their fathers. The more intelligent part of the Indians believe in one Great Father of all; also in evil influences, and in revelation and prophecy; and in many of their religious rites and ideas, I think they are quite as consistent as the Christian sects of the day."[21]

Hamblin kept a home in Kanab, Utah (Kanab's city park is named Jacob Hamblin Park[25]). Hamblin started a ranch in the House Rock Valley in the Arizona Strip at the base of the Vermillion Cliffs. Jacob Lake, Arizona, on the Kaibab Plateau north of the Grand Canyon is named after him, as is Jacob Hamblin Arch in Coyote Gulch and Hamblin Wash along U.S. Highway 89 in northern Arizona.

Hamblin also dug the first well outside of Las Vegas, and helped build the first Mormon mission there. One wall of that mission still stands just outside of Vegas, near an area called Indian Springs. (See Peterson, Charles S. (1975). "Jacob Hamblin, Apostle to the Lamanites, and the Indian Mission". Journal of Mormon History. 2: 21–34. ISSN 0094-7342. JSTOR 23286026.) Jacob received a vision, that he attributed to God, when his men and horses had run out of water just outside of Vegas. Jacob's brother had traveled ahead, Jacob's native guide was unfamiliar with that area and they could not locate water. Jacob had a vision, which his brother said he'd had since childhood, that vision showed a movie that led Jacob to where that spring was, and where he'd later dig the first well. This location is next to route 95 and what is now Area 51. (See also, Millenium Hospitality book series by Air Force enlistee Charles Hall, where a tall white woman known as "The Teacher" recounts when she tried to introduce herself to the first (Mormon) settlers in Las Vegas, as they sat around the campfire.) Hamblin, his brother and other Mormon settlers thought they were seeing the ghost of Jacob's second wife Rachel, who'd recently died after the Utah flood that washed their home away.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Early Latter-day Saints referred to Native Americans as "Lamanites," a term derived from the Book of Mormon.

- ^ "Hall of Great Westerners". National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ^ "JACOB VERNON HAMBLIN (pioneer, missionary)". Washington County Historical Society. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ Corbett, Pearson Harris (1952), Jacob Hamblin, The Peacemaker, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co, p. [page needed], OCLC 1399539

- ^ Miller, Vera Leib (1975), The Jacob Vernon Hamblin family, Tucson: Boyde Done Skyline Printing, p. [page needed], OCLC 33023754

- ^ Hamblin (1909), p. 13

- ^ Richard Van Wagoner,"The Making of a Mormon Myth: The 1844 Transfiguration of Brigham Young", "Dialogue : A Journal of Mormon Thought", 1995, Pages 1-24

- ^ Hamblin (1909), p. 29

- ^ a b Hamblin (1909), p. 41

- ^ Furniss, Norman F. (1960), The Mormon Conflict: 1850-1859, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale, p. 163, OCLC 484414

- ^ Walker, Ronald W. (2003), "'Save the Emigrants': Joseph Clewes on the Mountain Meadows Massacre", BYU Studies, 42 (1), archived from the original on 2013-10-21

- ^ Hamblin (1909), pp. 42–43

- ^ a b Hamblin (1909), p. 43

- ^ Linder (n.d.)

- ^ Thompson, A H; Gregory, Herbert E (2009), The Diary of Almon Harris Thompson: Explorations of the Colorado River of the West and Its Tributaries, 1871-1875, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press and Utah State Historical Society, p. [page needed], ISBN 9780874809626, OCLC 298778927

- ^ Hamblin (1909), pp. 43–44

- ^ "SurvivingChildren". www.mtn-meadows-assoc.com.

- ^ "Major Carelton's Report". www.mtn-meadows-assoc.com.

- ^ Hamblin (1909), pp. 55–56

- ^ a b McClintock, James H. (1921), Mormon Settlement in Arizona, Phoenix Arizona: Arizona Historian Office, p. 65

- ^ a b Hamblin (1909), p. [page needed]

- ^ Wixom (1998), p. [page needed]

- ^ a b Wixom (2008), p. [page needed]

- ^ Letter to the Pioche, Nevada Register dated Feb. 5, 1874, submitted by Mr. J. E. Smith [full citation needed]

- ^ "Jacob Hamblin Park, Kanab Utah". Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

References

[edit]- Compton, Todd (2013), A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary, Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, ISBN 9781607812340

- Hamblin, Jacob (1909) [1881], Little, James A (ed.), Jacob Hamblin: A Narrative of His Personal Experience, Faith Promoting Series (2nd ed.), Salt Lake City: Deseret News

- Haymond, Jay M. (1994), "Hamblin, Jacob", Utah History Encyclopedia, University of Utah Press, ISBN 9780874804256, archived from the original on November 3, 2022, retrieved May 7, 2024

- Linder, Douglas O., ed. (n.d.), "Testimony of Jacob Hamblin", Testimony in the Trials of John D. Lee, University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law, archived from the original on 2007-12-19

- Wixom, Hartt (1998), Jacob Hamblin: His Own Story, St. George, Utah: Dixie State College, OCLC 40390805

- Wixom, Hartt (2008), Jacob Hamblin: A Modern Look at the Frontier Life and Legend of Jacob Hamblin, Springville, Utah: CFI, ISBN 9781555172732, OCLC 35954246

External links

[edit]- Register of the Jacob Hamblin Journal, 1868-1886, a collection of Hamblin papers held at Brigham Young University's L. Tom Perry Special Collections

- The Jacob Hamblin Legacy Organization, Inc., a group of descendants of Jacob Hamblin

- The Jacob Hamblin Memorial Committee, a group of Southern Utah residents raising money to build a memorial to Hamblin in Kanab, Utah

- 1819 births

- 1886 deaths

- 19th-century Mormon missionaries

- American Mormon missionaries in the United States

- Converts to Mormonism

- People from Coconino County, Arizona

- History of the Latter Day Saint movement

- Mormonism and Native Americans

- Mormon pioneers

- Mountain Meadows Massacre

- People from Kanab, Utah

- People from Tooele County, Utah

- People of the Utah War

- People from Salem, Ohio

- Mission presidents (LDS Church)

- American leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Latter Day Saints from Utah

- Latter Day Saints from Ohio

- People from Santa Clara, Utah